Plot summary

A Latin-American insurgent and a black leader join forces to free an African nation. But they'll have to face a German mercenary aided by an American agent and a Portuguese advisor, all working for a mysterious woman.

Uploaded by: FREEMAN

Director

Tech specs

720p.WEB 1080p.WEBMovie Reviews

certainly not on the level of Godard!

I just saw this film in the cinema of the Austrian Film Museum and have to in one point contradict the reviewer from San Francisco: at least in Vienna, this film was IN COLOR. Theatrical tableaux, sometimes containing strong images, strung together with a generally only mediocre sense for time flow. It sometimes reminded me of the more didactic films of Godard, but often failed to come up to the technical level present even in Godard's most recondite efforts. Now and then I felt I was perhaps getting new insights; in other parts of the film I was just horribly bored and felt the director had little sense of how to effectively shape his material. Certainly no masterpiece, but, at any rate, I did wind up wanting to learn more about Glauber Rocha.

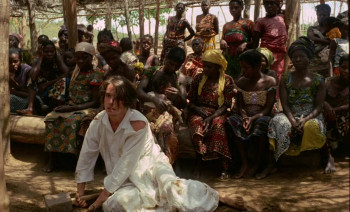

Tricontinental Cinema

Ironically, it was at the height of his fame as an exponent of a specifically cinema that Rocha was exiled from Brazil and began to operate within a European framework, seeking funding wherever he could. 'Antonio das Mortes' had effectively put Brazil on the international (read: European) cinematic map, providing a populist left-wing icon that combined the appeal of the 'Zapata westerns' with that of the left-leaning arthouse crowd, coincided with Rocha's (self-imposed) European exile, yet Rocha was now cut off from the folk practices which gave his early films their force: the cangaceiro myths of 'Antonio' and 'Black God', the cadomblé of 'Barravento'. His embrace of identity as a 'tricontinental' filmmaker, and consequent depiction of the Third World thus in turn becomes more generalised, at once suggesting solidarity along the lines of tricontinentalism, and reflecting an unmooring from the specificities of Brazilian cultural production. During the 1970s, Rocha shot films in the Democratic Republic of the Congo ('Der Leone'),Spain ('Cabezas Cortadas') Italy ('Claro') and, as part of a collective production, the documentary 'As Armas e o Povo' on the 1974 carnation revolution in Portugal. In other words, he participated in the political questions both of the European 'West' (including its dictatorial, military aspects) and the decolonising 'Third World'. Beginning with 'Der Leone', Rocha gives new meaning to the term 'international coproduction'. If this new confluence of state and private funding arose in part from the inability of national cinemas to compete with Hollywood, it also enabled the production of a notably left wing, third wordlist cinema-the 'Zapata westerns', films like Bertolucci's 'Novecento', Pontecorvo's 'Battle of Algiers' and 'Quiemada'. The film's cast is international and, though the film is shot primarily in French, each the five languages that form its title are also spoken. Rocha thus insists, while operating from a perspective informed by the particular experience of brazil, that the film is international, in terms of filmic influence-he mentioned Brecht, Einstein and godard in relation to this film, along with cinema novo-and the issues of colonialism, an international phenomenon. 'Der Leone' differs from almost all existing models of political cinema: the Maoist-but white and European-left found in Godard's work from 'La Chinoise'; realist depictions of revolution (Pontecorvo); neorealism; the attempt to create empathy for the struggles of the oppressed. Instead, he turns to allegory and dream, not just as one element, but as influence on total structure, at once stressing the technological mediation of cinema in a firmly materialist manner and insisting on the importance of an apocalyptic, revolutionary mysticism to its conceptualisation of politics, resistance, revolution. Thus, Rocha at once emphasizes the defamilisarising-'modernist'-elements of his previous work, bringng together a secular, materialist tradition-Brecht, Godard-with the ecstatic, the mystical and the musical that differed sharply from such models. If Rocha's Antonio films had borrowed their figuration from existing folk myth and, to a lesser extent, film trope-St George, the cangaceiro, the landowner, the cowboy-the allegorical canvas here is broader and more international. Unlike Godard-who avoided Africa-or Pasolini-whose African and Arabic settings were, to say the least, romanticised-Rocha took seriously the possibility of Africa as part of the tricontinental axis. His African extras are not anthropological specimens but real people, sometimes laughing at the actions they're asked to perform: in one key moment, the camera zooms past the European actors and lingers on the faces of the crowd who watch them with a kind of defiant bemusement that extends to the filmmaker himself. The scenarios sees the tricontinental revolutionaries-associated with Zumbi, the Black Brazilian founder of the quilombo community Palmares, with African leaders such as Cabral, and with Che Guevara-unite against Marlene, the Aryan figure identified with the seven-headed beast of the apocalypse and with the mendacious forces of money and European colonial ideology, and her henchmen-a series of European mercenaries and the neo-colonialist ruler from the African national bourgeoisie. At the films end, a procession of militants in guerrilla fatigue slowly march up the hill, singing a revolutionary song. The protagonists of 'White God', Paulo in 'Terra em Transe', or Antonio in 'Antonio das Mortes', who end those films stuck on the edges of things with no way out-the coast, the desert, the endless road-with no way out. Here, however, the militants, unlike those isolated figures, move as a group and march with a purpose, even if it's not clear where they're heading. Moreover, their song unites art and struggle: the song and the machine gun, the spear and the dance are connected. Rocha's exilic internationalism is thus refigured as space of possibility as well as the product of political catastrophe. At this point, there was evidently a world to win.